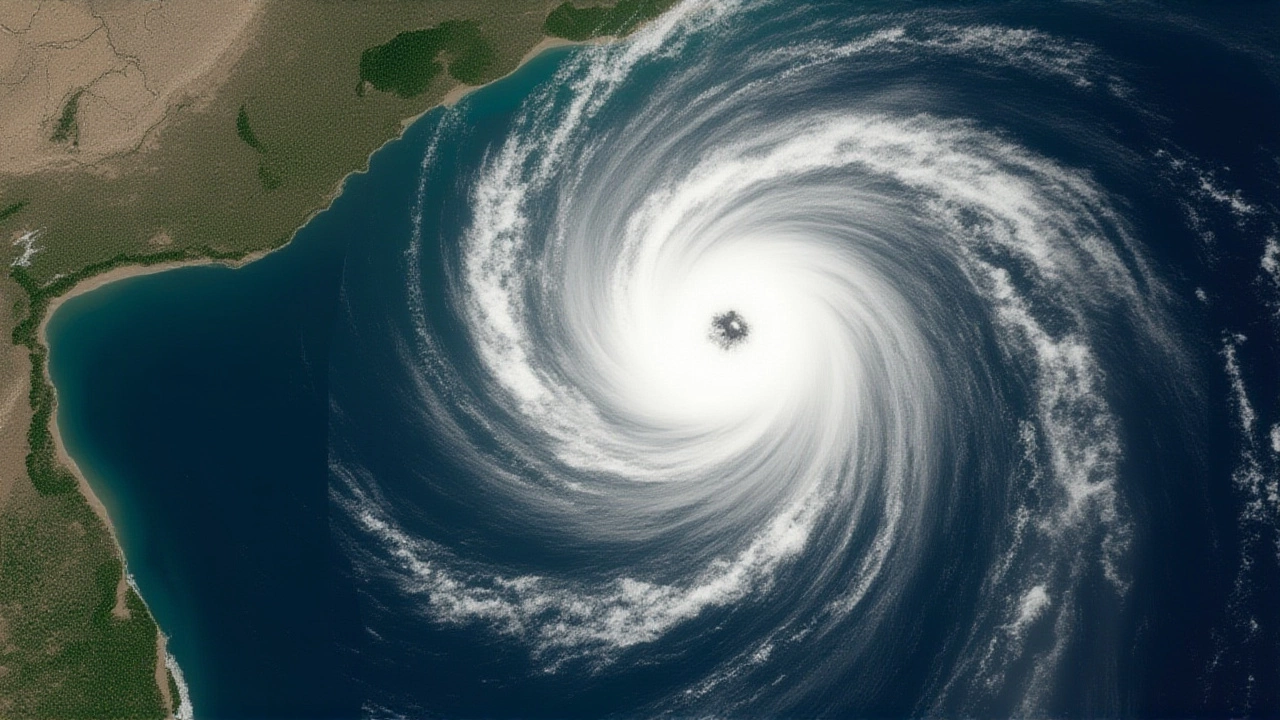

As the sky darkened over Visakhapatnam on the evening of October 28, 2025, the roar of wind and the drumming of rain signaled what meteorologists had feared: Cyclonic Storm Montha had made landfall along the Andhra Pradesh coast. The storm, which began as a modest depression east of the Andaman Islands just two days prior, surged with terrifying speed — packing sustained winds of 85 km/h and gusts that tore through palm groves and fishing nets alike. The India Meteorological Department (IMD), headquartered in New Delhi, had issued red alerts for 23 districts across Andhra Pradesh and neighboring Tamil Nadu, warning of life-threatening storm surges, flash floods, and rainfall exceeding 200 mm in isolated pockets. This wasn’t just another monsoon spell — it was the second major cyclone of 2025 to slam into India’s eastern seaboard, and the most intense since Depression ARB 01 hit Ratnagiri in May.

From Depression to Deluge: The Storm’s Rapid Intensification

What started as a low-pressure system on October 26, 2025, was upgraded to a deep depression by the IMD by 18:00 IST that same day. By the next morning, it had become a cyclonic storm. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) confirmed the system’s rapid development, noting a drop in central pressure from 998 hPa to 992 hPa in under 24 hours — a telltale sign of explosive intensification. By 05:00 IST on October 28, winds had climbed to 46–55 km/h, with gusts hitting 65 km/h. Within hours, models predicted a final spike to 80–90 km/h — just shy of severe cyclonic storm status, but more than enough to cause widespread devastation.

The Andhra Pradesh coastline, stretching 974 kilometers, bore the brunt. Coastal districts from Srikakulam in the north to Nellore in the south were locked in a battle against rising tides. Storm surge heights of 0.8 to 1.2 meters above normal tide levels were expected — enough to swallow low-lying villages near the Krishna and Godavari deltas, where rice fields stretch like green seas.

Emergency Response on Overdrive

The state government, led by Chief Minister Y. S. Jagan Mohan Reddy, moved with urgency. By 08:00 IST on October 28, the Andhra Pradesh State Disaster Response Force (APSDRF) had evacuated over 180,000 people from coastal hamlets. Fishing communities — often the last to leave — were given special priority. Over 387 relief camps were activated, stocked with 2,150 metric tons of food grains and 1.2 million liters of drinking water, as Governor Biswabhusan Harichandan confirmed during a press briefing in Visakhapatnam.

The National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) deployed 28 specialized teams — 672 personnel strong — armed with 140 inflatable boats, 112 high-capacity water pumps, and 56 rescue vehicles. Director General Atul Karwal stated the teams were positioned in strategic hotspots, ready to respond within 30 minutes of distress calls. Meanwhile, the Indian Navy Eastern Naval Command, under Admiral Rajesh Pendharkar, launched 12 offshore patrol vessels and 8 helicopters from its base in Visakhapatnam. “We’re not waiting for calls,” Pendharkar told reporters. “We’re going to where the water is highest.”

Transport, Agriculture, and the Silent Fallout

The economic toll began to show even before the storm’s eye crossed the shore. The Andhra Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation (APSRTC) suspended all coastal bus services. The South Central Railway canceled 47 passenger trains — affecting nearly 38,500 travelers — and suspended operations through October 29. Power lines snapped. Mobile towers went dark in 17 districts.

But the biggest casualty may be the harvest. The Andhra Pradesh Department of Agriculture estimates 127,000 hectares of standing paddy — worth ₹1,850 crore (about $221 million) — are at risk. The Krishna and Godavari deltas, which produce 65% of the state’s rice, are now under water. Farmers who planted just weeks ago, betting on a dry October, now face ruin. “This isn’t just about crops,” said Dr. Laxmi Rao, an agricultural economist at Andhra University. “It’s about next year’s seed stock, about debt cycles, about whether children will go to school after the harvest is gone.”

Space, Science, and the Watchful Eye

Behind the scenes, India’s scientific infrastructure was working overtime. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) deployed its Space Applications Centre (SAC) in Ahmedabad to feed real-time satellite imagery from INSAT-3D and Oceansat-2 to the IMD every 15 minutes. “We’re seeing the storm’s structure in unprecedented detail,” said Dr. Nilesh M. Desai, SAC’s director. “This isn’t just forecasting — it’s saving lives.”

The storm’s name, Montha, came from Thailand, as part of the World Meteorological Organization’s rotating list. It means “cicada” — a fitting, eerie metaphor. Cicadas emerge quietly, then drown out the world with their noise. So too did this storm — quiet at first, then deafening.

What Comes Next?

By October 30, 2025, Cyclonic Storm Montha is expected to weaken into a remnant low over Telangana, but its rains will linger. The IMD warns of continued heavy showers in interior districts through the weekend. Emergency teams are now shifting from rescue to recovery. The state has already requested ₹5,000 crore in central aid. Relief camps are being turned into temporary shelters. Water purification units are being airlifted.

And the question lingers: Why now? The North Indian Ocean cyclone season runs April to December, peaking in May and October. The 2025 season has already been above average — with three systems forming before October. Climate scientists point to warmer sea surface temperatures in the Bay of Bengal — up to 1.5°C above long-term averages — as a key driver. “We’re not seeing more storms,” said Dr. Priya Menon, a climate researcher at IITM Pune. “We’re seeing stronger ones. And they’re coming faster.”

Frequently Asked Questions

How many people were evacuated before Cyclonic Storm Montha made landfall?

Over 180,000 residents were evacuated from low-lying coastal areas across Andhra Pradesh, with special efforts focused on fishing villages and island communities. The Andhra Pradesh government activated 387 relief camps, housing evacuees with food, water, and medical supplies before the storm’s arrival.

Which districts were under the highest risk during the cyclone?

The 10 most critical districts in Andhra Pradesh were Srikakulam, Visakhapatnam, East and West Godavari, Krishna, Guntur, Prakasam, and Chittoor. In Tamil Nadu, Tiruvallur, Kancheepuram, and Chengalpattu were under red alert due to expected heavy rainfall and coastal flooding. These areas received the highest rainfall projections — up to 200 mm — and storm surges of over a meter.

What made Cyclonic Storm Montha different from other cyclones this season?

Unlike earlier systems, Montha intensified rapidly over the Bay of Bengal, fueled by unusually warm sea surface temperatures — nearly 1.5°C above average. It also tracked directly toward a densely populated coastline with limited natural barriers, unlike storms that weakened over land earlier. Its timing — just before the rice harvest — made agricultural damage particularly devastating.

How did satellite technology help during the cyclone?

ISRO’s INSAT-3D and Oceansat-2 satellites provided real-time, 15-minute updates on the storm’s structure, wind speed, and rainfall patterns to the IMD. This allowed for precise evacuation timing and resource deployment. For the first time, forecasters could track the storm’s eye movement down to the kilometer, reducing false alarms and improving response accuracy.

What’s the long-term impact on Andhra Pradesh’s agriculture?

An estimated 127,000 hectares of paddy — worth ₹1,850 crore — are damaged, with the Krishna and Godavari deltas hardest hit. These regions produce 65% of the state’s rice. Recovery will take months: farmers need new seeds, irrigation repairs, and financial aid. Without intervention, crop failure could push thousands into debt cycles, affecting food prices across South India.

Why was the storm named ‘Montha’?

The name ‘Montha’ was contributed by Thailand as part of the World Meteorological Organization’s rotating list of cyclone names for the North Indian Ocean. It means ‘cicada’ in Thai — a reference to the insect’s sudden, loud emergence. The name reflects how the storm appeared quietly but grew into a powerful, disruptive force.